TEL: 415.441.8680

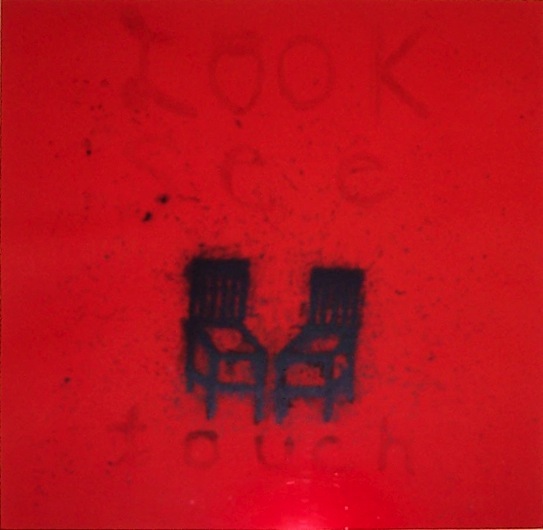

Look, See,Touch, 1991, woodcut and etching, AP (ed. 40), 23” 1/2 x 23” 1/2 (image)

Squeak Carnwath (born 1947 in Abington, PA) is a contemporary American painter. She received her MFA from California College of Arts and Crafts in 1977. She is a Professor of Art at the University of California, Berkeley, where she has taught since 1982, having previously taught at California College of Arts and Crafts and Ohlone College. She currently maintains a studio in Oakland, CA where she has lived and worked since 1970.

After high school, Carnwath studied art in Illinois, Greece, and Vermont before attending the California College of Arts and Crafts, where she studied ceramics, painting, and sculpture with Viola Frey, Art Nelson, Jay DeFeo, and Dennis Leon. Soon after graduating with an MFA, Carnwath began to receive recognition for her work including a Visual Arts Fellowship grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and a SECA Art Award from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which included a solo exhibition at the museum. Her work is also a part of the traveling multi-media art exhibit The Missing Peace: Artists Consider the Dalai Lama.

In 1996, Chronicle Books published a 108-page monograph titled Squeak Carnwath: Lists, Observations & Counting with essays by Leah Levy and James and Ramsay Breslin. In 2009, the professional association between artist Squeak Carnwath and Karen Tsujimoto, senior curator of art at the Oakland Museum of California, culminated in the exhibition Squeak Carnwath: Painting Is No Ordinary Object (April 25 through August 23, 2009). The exhibition's companion book, Painting Is No Ordinary Object, is a 160-page retrospective of Carnwath's career. It features more than 80 color reproductions and essays by Tsujimoto and art critic and poet John Yau (co-published by Pomegranate, 2009).

Carnwath has a distinctive and recognizable style which combines diaristic and personal elements with universal or existential themes. Her paintings "combine text and images on abstract fields of color to express sociopolitical and spiritual concerns." She has described herself ironically as a "painting chauvinist" due to an abiding preference for that medium, although she is also an accomplished printmaker and has created sophisticated Jacquard tapestries, artist books, and mixed media works in addition to her oil and alkyd works on canvas.

Squeak Carnwath is currently a tenured professor of art practice at University of California at Berkeley, after having taught at the University of California at Davis from 1983 to 1998. Through her professorship she has influenced hundreds of young artists in her three decades of teaching and art making. She has received fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

ABOUT THE ARTIST WORK

The color palette and the visual vocabulary—images of records, tree stumps, and stacked boxes, among other motifs, in combination with the artist’s diaristic text—are repeatedly reconfigured from one painting to the next in Squeak Carnwath’s work.

Repetition, in and of itself, is essential to the artist’s process. “Some people deal with trauma by repetition. Remaking the same thing over and over. The repetition is a comfort,” reads a section of text from one painting. In many ways, understanding this aspect of the work is more important than a voyeuristic deconstruction of the iconography, tempting though it may be to decipher the codes therein. “If there is a specific trauma, there isn’t any point in knowing what it was. All women are traumatized.

I have simply refigured out ways to use that anger,” Carnwath explains. “Repetition orients us to a place of well-being. I like to see what the possibilities look like and feel like. And I have to paint it. I can’t make a sketch or a smaller version of the larger idea. I am trying to get something right. I have to do it over and over again in full to make it feel right, to absorb it and own it.” Originally from Pennsylvania, Carnwath studied at Goddard College in Plainfield, Vermont before receiving her MFA from California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, California in 1977. Though widely recognized as a Bay Area painter, her work does not lend itself to any of the prescribed regional movements that specialize in figuration or landscape. Her paintings combine stylized realism and abstraction with figurative references and gestural marks. She began painting with oils as a young child and adheres to the theory, made popular by Malcolm Gladwell’s 2008 book “Outliers,” that 10,000 hours of dedication to a task yields mastery. (By her calculation, she has worked well beyond this time frame.) One might casually question her ability to paint with the skill of a master painter—after all her style of painting does not summon the work of the highly realist painters that we traditionally regard as masters. Or does it? Look closely at what appears to be collaged paper with hand-written text in so many of her compositions. There is no paper: it is all paint, even what appears to be graphite is paint. This small point of departure, between the skills she possesses and how she employs them, begs a closer consideration of the repetition from throughout her decades long career. The seriality gives visual form to the experience of meditation, the repetitive nature of the work providing the visual equivalent of a mantra.

Carnwath often works on ten large-scale paintings at a time in her Oakland studio, working back and forth between the paintings to realize their completion. Titles, denoted in block lettering along the left-hand side of each canvas, highlight the edges and suggest a sidelong consideration of the work in much the same way that one would peer through a doorway. “Enter here,” reads text writ large in one painting, inviting the viewer in.

“Painting preserves ephemerality and the fragile,” reads much smaller text from the same composition. The images of boxes and urns are like repositories for memories, grief, and guilt: the things that plague us. Whatever may be the personal experiences embedded into the paint, the work remains subjective. Their meaning is left open for interpretation. An irregular dashed linedemarks a “guilt free zone” in several of the works and by the artist’s own admission, this space is as much for her as it is for the viewer. But, she explains, “If I am painting, nothing is going wrong. Everything is going right.”

—CHRISTIAN L. FROCK

In an essay for a 2001 Flintridge Foundation catalog, Noriko Gamblin describes the evolution of Carnwath's approach to composition and subject matter:

“The work for which Carnwath first became widely known in the mid- and late 1980s is characterized by simple, iconic images and words floating like astral bodies within monochromatic or bichromatic fields. The images represent common things—chairs, vessels, bones, feet, genitalia, flowers, birds, houses, and so on—using rudimentary forms and emphatic black outlines. The words or passages of text, rendered in an ingenuous and expressive script, catalogue and comment on various aspects of existence, such as the affinities that unite seemingly unrelated objects and the essential differences (e.g., between that divide them. Simultaneously comic and grave in tenor, these pictures evoke the free-ranging ruminations of a daydreaming mind as it encounters the myriad phenomena of daily life and tries to make sense of them... engaging an ever-evolving constellation of preoccupations and investigations: how we know things, what we know, the nature of memory, perception, passion, time, and death.

Although Carnwath quickly established a distinctive personal style, some aspects of her work have undergone gradual transformations. The strongly geometric structure— characterized by grids, quadrants, and contrasting color bands and fields—of her paintings of the 1980s and early 1990s has loosened into more fluid arrangements of diverse elements, which include structural motifs as well as "decorative" patterns. Similarly, her iconography, which was initially tied to a relatively circumscribed personal symbology, has both expanded and grown more allusive. The early lists, litanies, injunctions, and poetic observations have been joined by more casual notations, which often lend a topical immediacy to her work.”

Source: Wikipedia

PARTNERS COLLECTION

SQUEAK CARNWATH

SCROLL DOWN

FOR ARTIST BIO

Contents Copyright © 2003-2013